Since the onset of the pandemic, we have seen an extraordinary display of corporate solidarity aimed at protecting employees and supporting customers and community. One such display has been the significant number of voluntary pay cuts taken at the executive level at hundreds of publicly-traded corporations in Canada and the U.S.

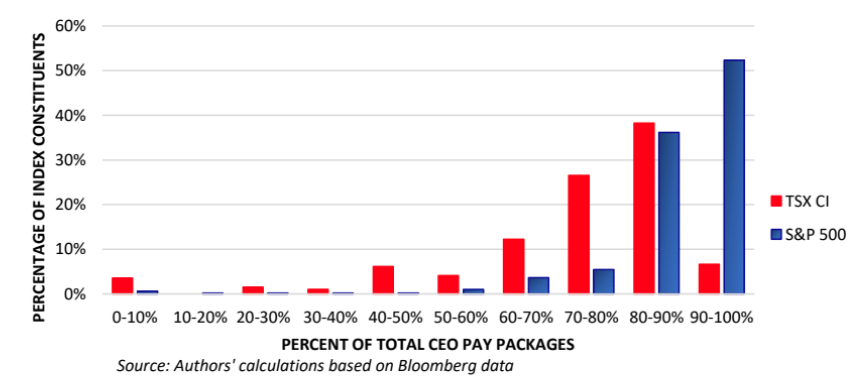

Though commendable at first glance, these pay cuts – most of which are temporary – are largely symbolic. Why? Because the cuts have been taken at the base salary level,[1] and base salary tends to make up only a tiny fraction of total executive compensation. The bulk of CEO pay, for example, is in the form of equity-based awards, which typically make up 80%to 100% of total compensation in North America, as shown in the chart below.

Figure 1: Distribution of Equity-based awards as a percent of 2019 CEO pay packages

In reviewing executive compensation in 2019, NEI found base salaries in Canada did not exceed $2.5 million;[2] and in the U.S, they did not exceed US$5 million. And some CEOs, such as those at Facebook, Akamai Technologies Inc. and Prologis (all company founders) earned just one dollar in base salary.

In reviewing executive compensation in 2019, NEI found base salaries in Canada did not exceed $2.5 million;[2] and in the U.S, they did not exceed US$5 million. And some CEOs, such as those at Facebook, Akamai Technologies Inc. and Prologis (all company founders) earned just one dollar in base salary.

However, factoring in equity-based awards increased CEO pay exponentially. Total CEO compensation reached as high as $24 million in Canada for the CEO of Restaurant Brands International; and in the U.S. the high was a whopping US$280 million for the CEO of Alphabet.[3]

Based on this evidence, it’s safe to say that when it comes to executive compensation a cut to base salary is really no cut at all.

Equity-based compensation is the monster we created

These findings are a stark reminder that the exceptionally wide (and growing) compensation gap between top executives and their employees is structural in nature – and it’s a structure we as investors helped create. Equity-based compensation was introduced by investors in the 1990s to help incent executives to lead their companies to increasingly higher valuations. And it worked well – too well. Executive compensation has skyrocketed and equity-based compensation is now viewed as a key contributor to income inequality, having helped concentrate wealth in the hands of the top 1% and widening the gap between executives and their employees.[4]

To rectify this situation – and it’s high time we did – we need to return to structural origins of executive compensation, and acknowledge that investors have been complicit in perpetuating this inequity. That means putting a stop to effectively turning a blind eye to excessive compensation in proxy voting and paying much closer attention to the evident negative societal impacts associated with excessive compensation. And it also means recognizing that while company values have climbed under this structure, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests excessive pay does not necessarily add value, and worse, that the opposite may be true.[5][6]

How much is too much?

Putting a dollar figure on the word ‘excessive’ is of course fraught with challenges. However, at NEI we believe it’s a necessary step that allows us to systematically vote the proxies of companies in our funds when it comes to compensation issues. We attempt to quantify ‘excessive’ from a societal perspective by setting a cap on total executive compensation when comparing it to the median household income in Canada and the U.S.

Today that means total compensation between $12.7 to $17 million at Canadian companies, and between US$22 million to US$25 million in the U.S. is considered excessive. We also recognize these thresholds will need to evolve in light of the growing societal impact of income inequality exacerbated by excessive executive compensation.

North American CEOs are amongst the highest-paid globally. Reflecting our longstanding concerns about the negative social and economic impact of income inequality, NEI sets a cap on the level of pay for CEOs or other executives that we can support in the U.S. and Canadian markets. Our test for defining very high quantum relates CEO total compensation to median household income, an indicator of the financial well-being of typical families. In the absence of any precedent to follow, we set our range of concern as follows:

- U.S. companies: 350 to 400 times the amount of the U.S. median household income – approximately U.S. $22 million to $25 million in 2020

- Canadian companies: 150 to 200 times the amount of Canadian median household income – approximately C$12.7 to C$17 million in 2020.

Different thresholds are used to reflect the reality of higher CEO pay and greater income inequality in the U.S. Examining the level of CEO pay in the broader societal context is one of the factors we use to assess executive compensation. We continue to apply our pay-for-performance voting guidelines to all compensation plans, whether or not the CEO pay falls in the range of concern that triggers additional scrutiny. For more details, please see our Proxy Voting Guidelines.

And you need to look beyond the topline numbers to really see that impact. Based on 2019 compensation levels, NEI’s cap identified excessive levels – some extremely excessive – for CEOs and/or executives at 12 companies listed on the S&P/TSX Composite Index and 67 companies on the S&P 500 Index. While relatively small in number, these companies significantly influence our economy and society, employing nearly 8.5 million people and representing about 21% of total S&P/TSX market capitalization and more than a third (US$10 trillion) of the S&P 500.

The problem is clearly bigger than it looks at first glance. The question is, where do we go from here?

The road to compensation reform starts with investors

We believe there is merit to de-emphasizing financial incentives for executives in favour of a more balanced structure to compensation –one that includes purpose–and sustainability-driven incentives tied to the successful improvement of working and living conditions for all stakeholders. This approach is, after all, the primary objective of the revised “Statement of the Purpose of a Corporation” backed by the Business Roundtable in 2019. The 181 CEOs who comprise the Roundtable committed to “lead their companies for the benefit of all stakeholders –customers, employees, suppliers, communities and shareholders”. Fixing executive compensation would be a great place to start.

And to reiterate, that start needs to focus on changing the structure of executive pay. While it’s tempting to reduce the inequality challenges posed by executive compensation to a simple equation – less pay for executives and more for the workforce – such actions would not likely impact stakeholders in any meaningful way, especially at the largest companies. For example, if the total pay package paid to Walmart’s five highest paid executives was reduced by 15%, that US$15.5 million distributed equally among the company’s 2.5 million workers would add up to only six dollars per year extra in the pockets of Walmart employees.

There are more effective and sustainable ways to use and re-allocate the capital. Creative solutions include enhancements to employee benefits, funding of employee trust funds, workforce education and training, paid internships and scholarships, and financing community initiatives with clear benefits to everyone.

Whatever the solution, it needs to start with investors demanding change. An initial step would be to shift the language investors use to vote on executive compensation packages by emphasizing more on a broader stakeholder alignment and incorporating societal impacts in pay level analysis. The status quo which narrowly focuses on shareholder value will only continue to negatively impact long-term investment performance, hinder economic growth and destabilize society, is no longer acceptable.

NEI will continue to report on the many challenges posed by executive compensation in a post-COVID world throughout 2020 and 2021.

Sources:

[1] From March to August 2020, over 600 companies in the Russell 3000 announced voluntary pay cuts for their executives and/or board members. In more than 70% of the cases, CEOs and top executives committed to cut their base salary by at least 20%, and 17% of the CEOs said they would give up or defer their total base salary for 2020. https://conferenceboard.esgauge.org/covid-19/payreductions, accessed September 9, 2020.

[2] Data source: Bloomberg

[3] Data source: Bloomberg

[4] PRI (2018). Why and how investors can respond to income inequality (p.33)

[5] Marshall and Lee, 2016 cited in Economic Policy Institute

[6] A study on the most overpaid CEOs in the S&P 500 found that the average annual total shareholder returns in the three years before a high pay package were essentially the same as those in companies without excessive pay. Then, in the nearly four years after the high payout, the group of companies with the most overpaid CEOs underperformed against the S&P 500. Retrieved from: As You Sow (2019). The 100 most overpaid CEOs: Are Fund managers asleep at the wheel? https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/100MostOverpaidCEOs_2019-1.pdf