There has never been anything like it before. 2024 is the year the first companies within scope will be legally accountable under the European Union’s (EU’s) Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). First reports are due in 2025 (based on fiscal year 2024 information). It is estimated that it will eventually also affect 1,300 Canadian companies directly, based on their business in the EU or listings on EU exchanges.

The CSRD is a European directive that marks a significant shift in the regulatory reporting environment as it sets out the rules for legally mandated accountability across a business’ entire value chain under the new and more robust European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). It is a reporting directive against the ESRS that embeds accountability for public and private companies to disclose actions taken to manage impacts on people and planet from business activities, and how the company is managing financially material ESG issues. The CSRD marks the beginning of a broader, sustainability regime designed to spur more proactive efforts and accountability to respect human rights and reduce carbon emissions and other environmental impacts linked to business activities. The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD or CS3D) is anticipated to follow once approved by European Parliament in April 2024. While the CSRD requires mandatory reporting against the ESRS, the CSDDD is a behavioural directive requiring companies to take action to prevent, mitigate, and remediate the most severe and likely adverse impacts from their business activities on people and planet. To ensure its passage following last minute erosion of support by multiple EU member states, changes to the CSDDD were negotiated in February and March 2024 to reduce its scope and scale so as to lessen direct impacts on small and medium-sized businesses. However it will still provide a legal liability mechanism for the largest companies operating in the EU to take responsibility for adverse impacts from business activities on society and the environment. In sum, this new sustainability regime is a gamechanger and has implications for entities even outside the EU. Below are high level answers to the following questions:

– What makes the ESRS unique?

– How will they affect Canadian companies?

– Why and how should Canadian investors encourage portfolio company alignment?

Key ESRS Features

| Double Materiality approach | Entities must report their most significant impacts on people and planet (impact materiality) as well as sustainability risks and opportunities (financial materiality). Based on the United Nations Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and the OECD Guidelines for Responsible Business Conduct. |

| Materiality Assessment | The ESRS starting point whereby companies must first detect and understand the most significant actual or potential impacts on people and planet across the entire value chain while also factoring in material risks and opportunities not related to the company’s outward impacts. |

| Scope | Applies to a company’s entire value chain (upstream supply chain, operations, and downstream customers) and requires enhanced reporting on both qualitative and quantitative information over short, medium, and long-term horizons. |

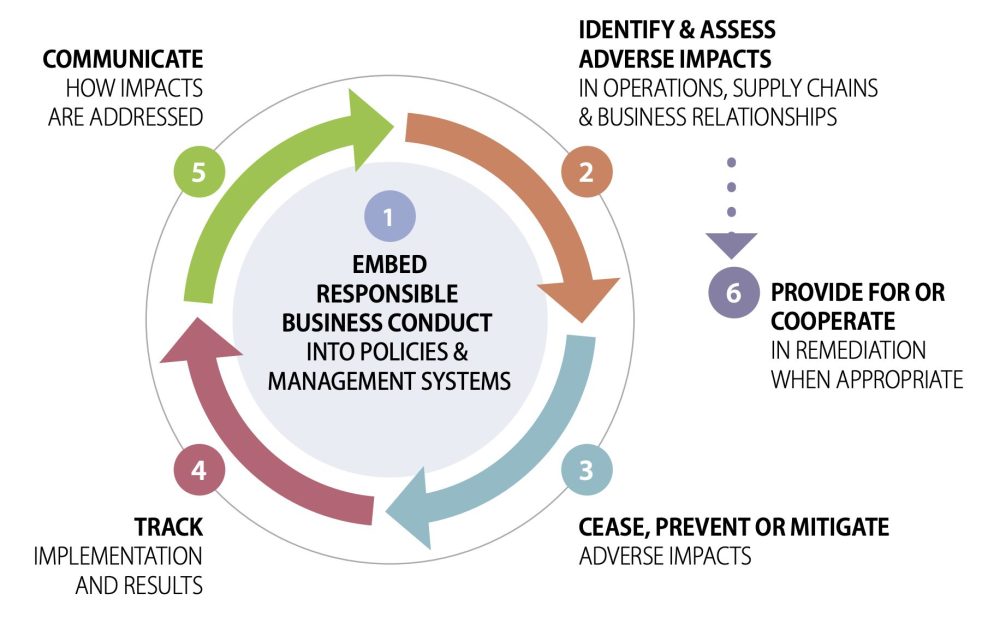

| Due diligence | Mandates disclosure of practices to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for the actual and potential most adverse impacts on people and the environment. This includes disclosure on how the views and perspectives of stakeholders and rights holders are ascertained and considered by senior management with respect to business model and strategy. |

| Assurance | Annual disclosures will initially require limited assurance by an accredited third-party auditor, expanding to reasonable assurance at a later date. |

ESRS key features

A double materiality approach is the defining feature of the ESRS and provides the criteria to determine whether a sustainability topic or information has to be disclosed in reporting. Impact materiality refers to an entity’s material actual or potential, positive, or negative impacts on people and the environment while financial materiality refers to whether a sustainability topic generates risks or opportunities that impact an entity’s financial performance or position. Under ESRS, double materiality is the union of both these concepts. Adverse impacts on people and planet may not immediately pose a risk to a company’s bottom line but can become financially material over time.

The ESRS require companies to disclose methods and results of a materiality assessment of the entire value chain to ensure detection of the most significant (positive or negative) impacts from business activities for prioritization in management regardless of near-term financial materiality. This mirrors the fundamental first step in a do no harm, human rights due diligence process aligned with the OECD Guidelines for Multinationals and the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Created in 1976 and 2011, respectively, these frameworks were developed and updated over the years to promote respect by businesses for international human rights laws, like the International Bill of Human Rights, which to varying degrees have been adopted into country laws around the world to hold states accountable to respect human rights. The CSRD, CSDDD and the ESRS now represent a new layer of accountability in that they legally enforce expectations for businesses to be accountable for respecting international human rights norms. This is by design. There are a considerable number of companies around the world already voluntarily committed to implementing the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines. Once transposed into the respective EU Members’ respective national laws, the CSRD and CSDDD will reinforce, and mainstream through hard law, already established, but voluntary, international human rights standards and frameworks to promote responsible business conduct.

How does this compare with other large sustainability reporting frameworks? The ESRS seek additional comparability and consistency for topical disclosures through alignment to the greatest extent possible with other international topical standards developed by the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). It should be noted, however, that the ESRS go extensively further than these frameworks because of the double materiality requirement.

The ESRS 12 topical standards are captured under four pillars as displayed in Figure 1. Note that social topical standards are broken down by stakeholder categories centring the need for careful consideration and prioritization of material impacts on these respective groups. Topical standards assessed by the company determined not to be material can be omitted. For each material topic, disclosure is required on:

– Business model and strategy. This includes reporting of baselines and time-bound targets, progress made toward targets, related company policies, actions taken to identify, monitor, prevent, mitigate, and remediate any actual or potential adverse impacts related to the matters in question, the result of these actions, and any relevant metrics.

– Governance. This includes disclosure of diversity and skills to manage material sustainability matters at senior levels, how oversight is operationalized, whether there are dedicated controls and procedures applied to the management of impacts, risks and opportunities, how these are integrated with other internal functions, and how all of the above are factored into executive compensation.

| General standards | Environmental standards | Social standards | Governance standards |

| 1 – General requirements 2 – General disclosures |

E1 – Climate change E2 – Pollution E3 – Water and marine resources E4 – Biodiversity and ecosystems E5 – Resource use and circular economy |

S1 – Own workforce S2 – Workers in the value chain S3 – Affected communities S4 – Consumers and end users |

G1 – Business conduct |

How will they affect Canadian companies?

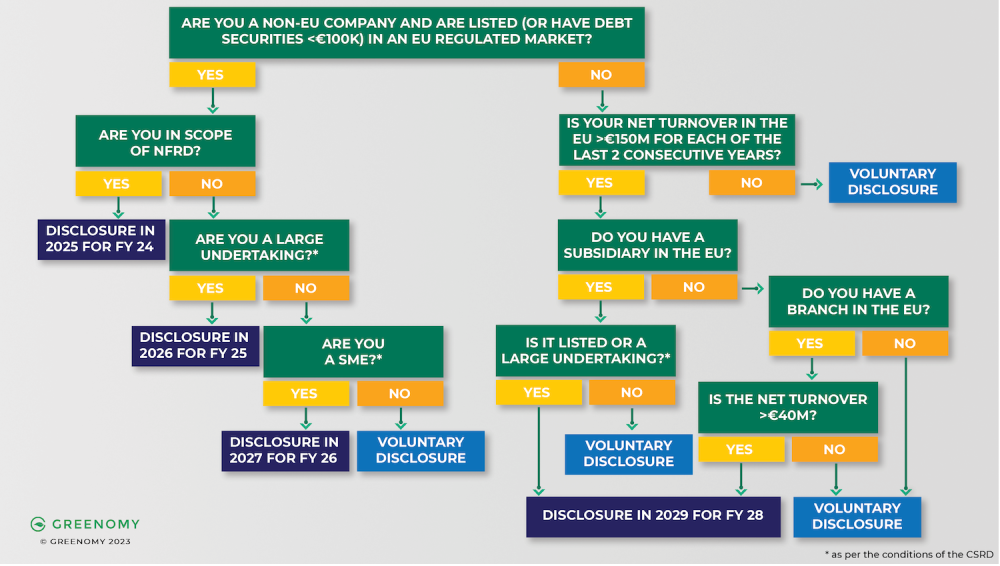

While the CSDDD will take longer to implement, the CSRD has already been enacted. Unlike the CSDDD, its scope provisions are wide, however, reporting obligations will be gradually implemented over the next five years (see Figure 2 below). It is anticipated it will eventually affect approximately 50,000 EU based companies, and around 10,400 foreign based companies directly, of which roughly 3,000 are American, 1,100 are British and 1,300 are Canadian. Indirectly, it will affect many more. Even if businesses do not have direct obligations under the CSRD they may still be asked for related disclosure by EU-based corporate customers, suppliers, lenders, and investors because the ESRS require companies within scope to report on human rights due diligence practices for their entire value chain.

Figure 2 provides a snapshot of the gradual implementation of CSRD obligations for non-EU based companies. Large Canadian entities who already report under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and are listed on an EU regulated market will be required to disclose in 2025. Resources to help you understand which and when non-EU companies will be accountable under the CSRD can be found here.

Companies that have already implemented voluntary practices that align with the UNGPs and or OECD Guidelines will have an advantage with respect to ESRS. They will have processes in place to detect and understand their most significant, and therefore material, impacts as well as their obligation to prevent, mitigate, and remediate adverse impacts from business activities in addition to status quo financially material issues.

Already, some Canadian companies that are not directly within scope of the CSRD have begun implementing such practices to varying degrees. For example, certain Canadian miners with a large global footprint and as suppliers of the raw materials used in the manufacturing of a wide array of essential goods around the world, including by customers in Europe, are getting ahead of regulation by developing public policy and implementing practices aligned with the UNGPs. This sector in Canada appears to be leading in its understanding of the long-term implications of Europe’s new and robust sustainability regulation on future growth prospects and subsequently, for business practices. But there is still a lot of work to be done to ensure accountability. Investors can play a role.

Figure 2: CSRD reporting for non-EU companies: What you need to know.

Note: Net turnover threshold was increased from €40 to €50 million. Non-EU parent companies of EU listed or based subsidiaries must provide consolidated ESRS aligned disclosures.

CSRD non-EU scope requirements will evolve over 4 years

Disclosure due in 2025 for FY 2024:

Large non-EU companies (more than 500 employees) with securities listed on an EU-regulated market (with the exception of micro-enterprises).

Disclosures due in 2026 for FY 2025:

Large* non-EU companies listed on an EU-regulated market.

Disclosures due 2027 for FY 2026:

Certain non-EU small and medium sized enterprises (“SMEs”) listed on a regulated market in the EU.

Disclosure due in 2029 for FY 2028:

Non-EU companies that have net turnover in the EU > € 150M for prior 2 consecutive years

Non-EU company that has a subsidiary in the EU that is either listed or considered a ‘large’ undertaking.

*Large as per CSRD is exceeding two of the following three metrics on two consecutive annual balance sheet dates:

– Total assets of €25M

– Net revenue of €50M

– Average 250 employees or greater

NOTE: Non-EU parent companies of EU listed or based subsidiaries must provide consolidated ESRS aligned sustainability reports. There are also a number of reporting exemptions for non-EU companies reporting under different regimes, however, these haven’t yet been finalized.

Why and how investors should encourage portfolio company alignment now

By May 31, 2024 a broad swathe of Canadian companies and institutions are required to report on their efforts to prevent and reduce their risk of using forced or child labour directly or in their supply chains, as per Canada’s newly enacted Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act. While this act is a mere drop in the bucket compared to the depth of Europe’s mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence accountability regime, companies can use it as a prime window of opportunity to ready and test their human rights-related policies, processes, and oversight mechanisms in case they need to report under CSRD or as part of a supplier or service provider of a company reporting to CSRD. Where to start? Voluntary commitment to and adoption of the UNGPs.

In early 2023 BMO Global Asset Management published a deep dive research report that found that Canadian companies are in early stages of readiness for alignment with the UNGPs. Canadian companies make decent voluntary policy commitments but can improve on implementing human rights due diligence. Given that the ESRS, which makes the UNGPs and human rights due diligence mandatory, is an indication of the future direction of travel of what will be considered the highest bar in a global marketplace, investors can help Canadian companies maintain their competitiveness.

Investors can encourage best practices through:

1) Education (if not already aware) on international human rights standards (such as the International Bill of Human Rights, UNDRIP, and others) and frameworks for human rights due diligence (UNGPs and OECD Guidelines).

2) Development of investor human rights policies that set clear expectations for alignment with international human rights standards and frameworks in investment decision making and investee company practices.

3) Development of systematic investor human rights due diligence procedures to implement policy commitments on human rights and ensure investors do not contribute to adverse impacts.

4) Engagement with investee companies on human rights policies and practices e.g., asking companies what their most significant positive and negative impacts on people and planet are throughout the value chain and what they are doing to prevent and mitigate negative impacts.

5) Communicate investor expectations to investee companies and use investor leverage to encourage adoption and implementation of practices that align with international human rights standards and frameworks that will simultaneously help future-proof companies against the EU’s new robust sustainability regime and any other similar regulations in other regions that may evolve over time.

Contributor Disclaimer

This communication is intended for informational purposes only and is not, and should not be construed as, investment, legal or tax advice to any individual. Particular investments and/or trading strategies should be evaluated relative to each individual’s circumstances. Individuals should seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding any particular investment. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Any statement that necessarily depends on future events may be a forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of performance. They involve risks, uncertainties and assumptions. Although such statements are based on assumptions that are believed to be reasonable, there can be no assurance that actual results will not differ materially from expectations. Investors are cautioned not to rely unduly on any forward-looking statements. In connection with any forward-looking statements, investors should carefully consider the areas of risk described in the most recent simplified prospectus.

BMO Global Asset Management is a brand name under which BMO Asset Management Inc. and BMO Investments Inc. operate.

®/™Registered trademarks/trademark of Bank of Montreal, used under licence.

RIA Disclaimer