A storm has come. People have sheltered at home as a pandemic has claimed lives across the planet and ravaged businesses, economies and social norms.

But humanity has weathered severe crises before – and is doing so again. As a species, we are survivors. We adapt. At this stage of the crisis, the short- and long-term consequences for individuals, families, businesses and politics are hard to calculate, and a second wave of infections remains a threat. We are learning to overcome a new enemy. Yet humanity will have to summon all of its adaptive ingenuity to combat the bigger storm coming our way.

The planet breathes

The coronavirus pandemic remains, first and foremost, a human tragedy. Yet the lockdowns briefly had positive environmental side effects. Declining industrial production improved air quality in even the most polluted regions, while grounded aircraft and reduced road traffic lowered levels of noxious fumes and carbon dioxide emissions.

Waterways, rivers and seas in popular tourist areas became clearer – the Venetian canals, for example, were reportedly the cleanest in living memory. In India, the Himalayas became visible from the Jalandhar district of the Punjab. In the absence of people, leatherback sea turtles returned to Florida beaches.

These signs that nature can quickly recover from the rapid pace and high consumption of modern living offers some encouragement that humanity could wind back the clock. But the scale of the tasks before us – to mitigate and adapt to climate change – is vast. Even more overwhelming is the short timeframe in which we must achieve both of these outcomes.

Is there an appetite for change?

Before the coronavirus locked down populations, CO2 emission rates looked set to increase global temperatures by 1.5°C and 2°C over the next 12 and 25 years. These estimates may even be optimistic, given they exclude feedback loops like the melting Arctic permafrost.

Even after accounting for the commitments by governments and companies to cut carbon emissions sufficiently, the accepted paradigm of continuous economic growth runs the risk of sentencing the world to a much warmer – and scarier – future.

Long-term bond yields suggest that we face decades of sub-par growth. In this environment, people are unlikely to support green efforts to drive down emissions that could further depress growth.

Climate calibration

Across the world, it’s getting warmer. If efforts to mitigate climate change prove insufficient or ineffective, rising temperatures could seriously affect sea levels, the food chain, human health and livelihoods. Most at risk are India, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Pakistan, Thailand and Vietnam – countries classified as among the warmest and most humid (already).

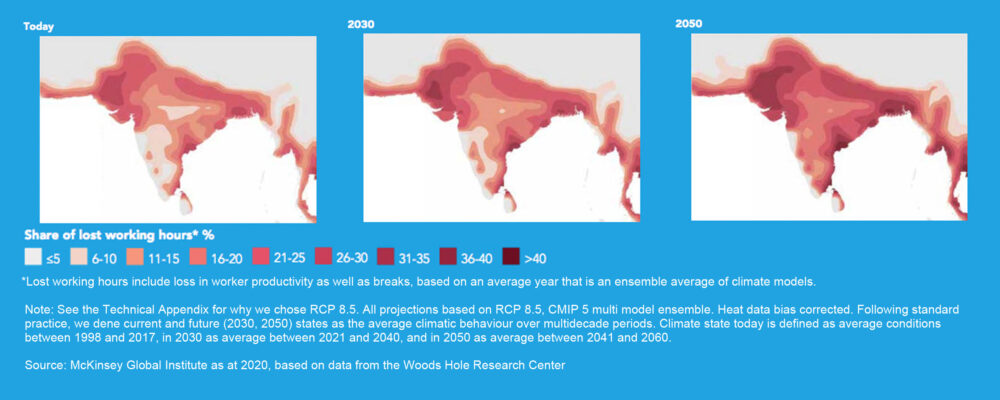

Consider India – where 42% of the workforce are employed in the agricultural sector and 3.8% in construction – which stands to lose the most as the number of days with insufferable heat climbs. Among labourers, the effective number of outdoor daylight work hours lost in an average year could increase by 15% in 2030, leading to a 2.5-4.5% drag on GDP.

Already about 10% of Indians, or 120m people, live in areas with a risk of lethal heat waves – defined as three-day surges in temperatures that exceed the threshold of survivability for a healthy human being in the shade – annually, and this proportion is expected to increase. By 2030, between 160m-200m of the Indian population will be exposed to this danger, and among them an estimated 80m-120m don’t have airconditioned homes.

The number of people expected to fall into this lethal danger zone is forecast to range between 310m and 480m by 2050. While it is true that most of the population is expected to live in air-conditioned accommodation by then, absent technological innovations, air conditioning will contribute to further heating up the environment.

Figure 1. The projected number of working hours lost* due to greater heat and humidity in India and South Asia

The next tier of countries impacted by climate change includes Indonesia, The Philippines, Saudi Arabia and Japan. While the latter is not part of the emerging markets benchmark, it remains economically important to the Asian region. China, Brazil and Chile enjoy diverse climates and thus have more varied levels of risk. Some are severe but due to the variance in their geographies (and economies) may cope better with climate change.

Overheating businesses

Emerging-market businesses are particularly vulnerable, given their generally high numbers of outdoor workers and low levels of savings and income relative to developed markets. Not only the productivity of businesses will be impacted, but also the capacity for some to remain operational if their current locations become too heat exposed.

Based on our analysis and engagements, we have determined that the companies in our emerging-market portfolio have not paid adequate attention to the risks that a global average temperature rise of between 2°C-4°C may pose to their businesses.

We recognise that boards and management teams already field plenty of ESG-disclosure requests from investors, in addition their day jobs of providing financial and strategic updates, and thus are feeling stretched as new requests for information and business adjustment come in. Keeping up with an ever-moving target of “sustainability” is difficult and further demands may be seen as inconvenient. But as long-term investors, we believe that adapting to climate change is more than a sustainability challenge: it is set to become one of survival. Through our engagements, we encourage the companies we invest in to prepare for a hotter world and assist where we can.

How can investors respond?

We believe that unfortunately, society’s efforts to prevent the earth from warming are not destined for outright success. Given this, we think that investors should pay as much attention to adaptation as mitigation. Adaptation can be defined as the measures that nations, cities, companies and individuals must take in order to prepare for living in a degraded environment. It may include large-scale capital projects or even the relocation of essential infrastructure and populations, and we need to consider the implications of these now.

Global warming is a vast problem. We can help to dissect the issue, as the McKinsey Global Institute has, by defining five key dimensions:

- Liveability and workability: Outdoor workers and people lacking savings or adequate income will be most impacted. Disease vectors will shift.

- Food systems: Flood and drought can cause breadbasket failures or reduce crop yields.

- Physical assets: Real estate and infrastructure could be damaged by flooding, extreme storms and wildfires.

- Infrastructure services: Heat, wind and flooding can disrupt power, water and transportation services.

- Natural capital: Disruptions to ecosystems can endanger food chains, habitats and economic activity.

Anthropogenic adaptation

Ever since humanity emerged in its current form 300 millennia ago, we have adapted to withstand a wide range of threats – war, disease, famine, natural disasters, economic depression and terrorism – and have often used the experience and knowledge gained in order to improve the lives of future generations.

But the anthropogenic phenomenon of global warming will test our ability to avoid mortal danger more than ever before. Humanity’s ability to adapt, something we have excelled at, must again come to the fore.

We encourage all investors to make climate change a core theme of their interactions with businesses: all companies, not only those we invest in, must begin to focus on adapting for the rougher weather ahead.

To find out more about how global emerging markets can adapt to this new normal, read the full Q2 2020 issue of Gemologist.

Sources:

[1] “Emission budgets and pathways consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C,” by Ricard J. Millar et al.,published by Nature Geoscience, volume 10, in 2017. Quoted in “Climate risk and response: physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts,” published by McKinsey Global Institute in January 2020, on p.35

[2] “Climate risk and response: physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts,” published by McKinsey Global Institute in January 2020