Food prices are rising everywhere. While food insecurity is a global trend stemming from several strong macro-economic forces at play, certain unique market characteristics could be exacerbating the problem within Canada. If incomes fail to keep up with inflation, Canadian food insecurity is expected to worsen further. We outline the situation and suggest 7 actions investors can undertake to tackle the issue.

Why food insecurity should matter to investors

The World Food Programme estimates 345.2 million people around the globe will be food insecure in 2023, more than double the number estimated in 2020. Statistics Canada data showed that in 2021, 5.8 million Canadians (1.4 million of which were children) across ten provinces were living in food-insecure households. Use of food banks rose 35% between 2019 and 2022 and it is estimated that food banks and other non-profits dispensing free food will see another 60% increase in demand in 2023. Experts believe the problem of food insecurity is expected to get worse if incomes fail to keep up with inflation. Without significant change, food insecurity will become a larger issue in Canada and globally.

Addressing food security and hunger, in addition to being a moral imperative, is an investor issue. The 2023 World Economic Forum Global Risks Report lists the cost-of-living crisis as the number 1 risk in the next two years to the global economy. At a global scale, food shortages and rising food prices are linked to social unrest, which can lead to destabilization of markets. A prime example of this were the “food riots”: in 2011 when the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Food Price Index peaked, and riots erupted in 48 countries. For reference, the FAO Food Price Index has never been higher than in May 2022, even when compared to the 2011 peak.

While it is unlikely that food insecurity in Canada will lead to social unrest at home, it does have negative knock-on effects. High food prices and inflation for many reduces the ability to save money. When grocery prices dramatically increase, Canadians’ ability to save money for retirement, school or for emergencies, is also reduced. Retail investors under financial strain might prioritize household spending over mutual fund investing. A reduction in discretionary spending by Canadian consumers can also negatively affect revenue of corporate issuers investors hold.

The price of food in Canada

As of January 2023, grocery prices in Canada had risen 11.4% compared to the previous year – almost double the overall inflation rate of 5.9%. There are many contributing factors. Covid-19 and geopolitical conflict have disrupted supply chains while climate events are challenging status quo means of agriculture and quantity of food produced. Escalating energy and fertilizer costs are also contributing factors.

In 2021 and 2022, grocery chain profits in Canada increased significantly amidst rising global inflation. Research examining the trend highlights how some of the Canadian grocers posted higher profits in the first half of 2022 relative to average past performance over the last five years.

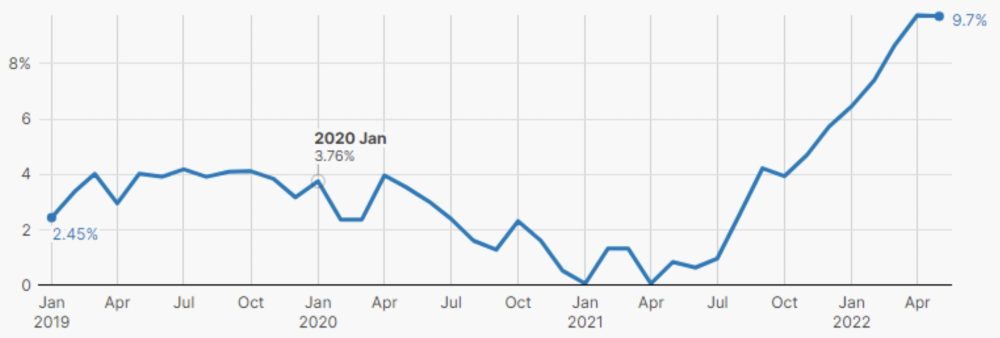

Grocery Inflation

Statistics Canada reports that while year-over-year inflation is 7.7 per cent for all products, groceries have gone up 9.7 per cent.

Source: StatCan CPI food purchased from stores.

Toronto Star Graphic

There are calls for greater transparency from the grocers on the link between rising food prices, supply chain costs and where the rising profits come from. The major grocers themselves note that excess profits can be attributed to sales in non-food segments such as makeup and pharmacy products, not to only from increases in food prices, and that they are in fact taking on more costs than they are passing on to the consumer. Enhanced disclosure by operating segment to give better insights into whether profits are coming from the pharmaceutical business, grocery business or elsewhere, could give away competitively sensitive information. However, seeing the numbers to verify the source of profits would help dispel concerns.

Under current practices, Canada’s major grocers do not disaggregate disclosures by operating segment (i.e. food versus non-food items) despite International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) requirement that disclosures be disaggregated if the nature of the products and services, and the means by which they are produced, are dissimilar. Investors can use their position of influence to encourage grocery retailers to enhance disclosure, mitigate food price-related risks and contribute to tackling food insecurity.

Canadian market dynamics and the Grocery Code of Conduct

Five large retailers control approximately 80% of Canada’s grocery retail market. The Canadian Competition Bureau is currently investigating whether competition in the sector is playing a role in the increase of grocery prices, with their report expected in June 2023. Some expect the bureau to recommend that the federal government create changes in the law to give it more power to address competition concerns.

Food supply chain complexities within Canada, including provincial border tariffs, also keep certain food prices artificially high or in some cases leads to forced food loss (see the Spotlight section).

| Spotlight The Canadian dairy, poultry and egg industry is a prominent example which showcases the difficulties of working in Canada’s food supply chain. Canada has a highly controversial supply-management system which regulates supply and imposes high border tariffs on taxes for these three food groups. This system, while in theory protects Canadian farmers, has been shown to have flaws, and is not holding up to the socio-economic pressures arising from high inflation. Dairy farmers, for example, are forced to dump milk in order to keep market supply levels within set quotas. Recently, these dairy farmers have been speaking out against the ‘milk-dumping’ policies, saying that more supply could lower prices. Additional supply could also potentially alleviate pressure on food banks. |

Furthermore, an estimated 12% of Canada’s avoidable food loss and waste occurs during the retail phase of the supply chain. Grocery retailers can play a key role in reducing food loss and waste including through influencing their supply chains, for example through procurement practices.

Concern that uneven power dynamics between grocery retailers and suppliers undermines the resiliency of Canada’s food supply chains has also led to efforts to develop a Grocery Code of Conduct to enhance transparency, predictability, and fair dealing within the sector. The voluntary Code’s anticipated release is by the end of 2023. One of the code’s intentions is to establish more equitable administration of retail fees that suppliers pay retailers to sell their goods. Current practices have been characterized as retroactive, unpredictable, and unilateral (the latter of which places smaller suppliers at a significant disadvantage) undermining conditions to support greater product variety, innovation, and supply chain resiliency in Canada.

While a Grocery Code of Conduct will not directly regulate prices nor fees that retailers set for food processors, it will establish contractual obligations for greater risk sharing including requiring more collaborative forecasting of supply orders.

The Code will also include a dispute resolution mechanism, adjudication process, mediation and arbitration models, and enforcement mechanisms, all of which will help promote fair and ethical trading between Canada’s grocery retailers and suppliers that ultimately help support greater domestic supply chain resiliency. A Grocery Code of Conduct can also help promote better worker conditions within Canada’s food supply chains by creating greater stability to support, for example, provision of a living wage and safe working conditions.

What can investors do?

Investors benefiting from higher grocery retail profits have their own obligation to conduct due diligence with investee grocery retailers accordingly to ensure that short term gains are not being prioritized over the longer-term implications that acute food inflation could have on returns across all portfolio investments.

Investors can encourage 7 best practices with companies both up- and downstream the food value chain and with policymakers:

1) Engage with Canadian grocers and food distributors to encourage more transparent disclosures aligned with the IFRS standards, which would create more transparency on profits by segment.

2) Encourage investee grocery retailers in Canada to proactively contribute and adhere to the principles within the upcoming Grocery Code of Conduct.

3) Given that food insecurity is expected to get worse if incomes fail to keep up with inflation, engage companies across portfolios on committing to providing Living Wages. Also consider support for initiatives such as the Workforce Disclosure Initiative, which creates reporting standards for companies on workforce matters including wage levels and benefits.

4) Encourage investee grocery retailers to implement effective human rights due diligence practices (HRDD) to prevent and mitigate actual or potential adverse human rights impacts from business activities. Under an HRDD approach, companies would need to investigate what adverse impacts operations have across the value chain. Access to food as a fundamental human right would be a key salient topic for companies in the food retail sector.

5) Keep an eye out for the Canadian Competition Bureau’s report in June to identify whether there are policy engagement opportunities based on its recommendations and advocate for human rights-based food policy with governments.

6) Encourage companies to advocate within their industry for more favourable market dynamics in Canada, which could help to lower food prices (such as in the example of the dairy, poultry and egg industry).

7) Encourage food retailer practices to reduce food waste and to donate excess food to food banks in line with the Canadian government’s recommendation for reducing food waste between food retailers in Canada.

Access to food is a fundamental human right and is embedded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As responsible investors whose approach includes investing or engaging for sustainable outcomes, we can take actions such as the ones above to contribute to the second UN Sustainable Development Goal to reach ‘Zero Hunger’ by 2030, both abroad and at home.

Contributor Disclaimer

Any statement that necessarily depends on future events may be a forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of performance. They involve risks, uncertainties and assumptions. Although such statements are based on assumptions that are believed to be reasonable, there can be no assurance that actual results will not differ materially from expectations. Investors are cautioned not to rely unduly on any forward-looking statements. In connection with any forward-looking statements, investors should carefully consider the areas of risk described in the most recent prospectus.

This article is for information purposes. The information contained herein is not, and should not be construed as, investment or legal advice to any party.

BMO Global Asset Management is a brand name under which BMO Asset Management Inc. and BMO Investments Inc. operate.

®/™Registered trademarks/trademark of Bank of Montreal, used under licence.

RIA Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view or position of the Responsible Investment Association (RIA). The RIA does not endorse, recommend, or guarantee any of the claims made by the authors. This article is intended as general information and not investment advice. We recommend consulting with a qualified advisor or investment professional prior to making any investment or investment-related decision.